Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

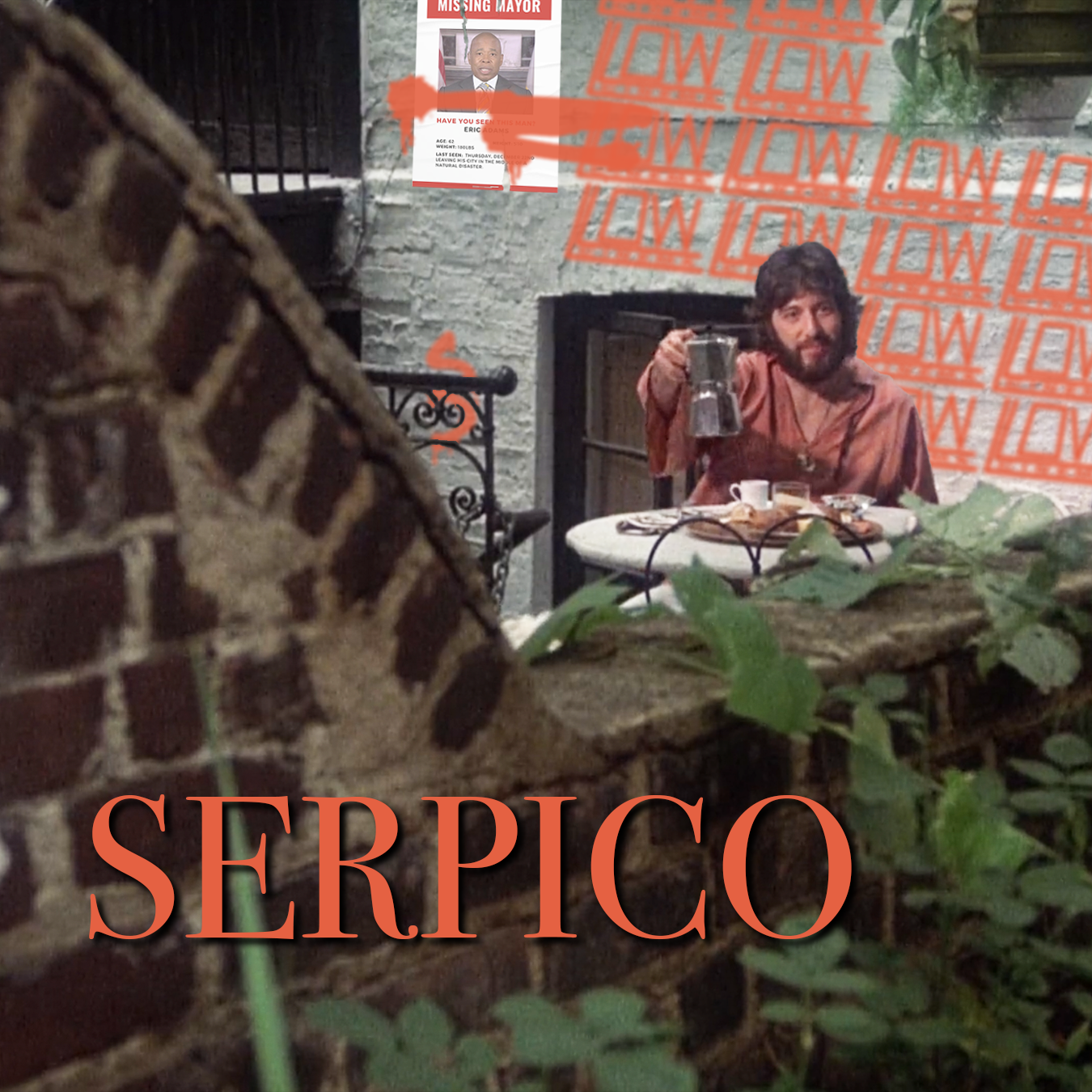

Serpico

Dir. Sidney Lumet, 1973, USA, 130 min.

If you haven’t seen Sidney Lumet’s classic 1973 biopic of cop-turned-anti-corruption-crusader Frank Serpico — a piece of cinema so gritty and unflinching that its position among the greats of fiscal-crisis-era New York movies is practically set in stone —you can be forgiven. After all, you’ve had to witness a similar clown show throughout Eric Adams’s mayoralty. The days of the Knapp Commission, the investigative body that Serpico’s revelations brought about, may be over, but the most bloated police department in the country doesn’t seem to have learned its lesson. Just two months ago, Thomas Donlon, one of Adams’s erstwhile police commissioners (of which Adams has cycled through four in as many years) filed a federal lawsuit against the department, which, pulling no punches, he called “A coordinated criminal conspiracy” that is “criminal at its core.”

Of course, aside from Serpico’s eerie political relevance even half a century later, it also stands out as a convergence of many talented filmworkers’ crafts. Al Pacino, who would reunite with Lumet two years later for Dog Day Afternoon, gives a master class in the Strasbergian method, his performance at once so raw and so measured that it gave chills to even the most jaded critics. Screenwriters Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler contributed other titans into the pantheon of New York City cinema, titles no less seminal than Midnight Cowboy and Saturday Night Fever. And cinematographer Arthur Ornitz would go on to lens equally iconic — if somewhat mutually antithetical — portraits of the city in Death Wish and An Unmarried Woman.

But perhaps one of the most singular pleasures of watching Serpico today is its unmatched value as a time capsule of Gotham’s urban fabric in the early 1970s. Shot on location in four out of the five boroughs (sorry Staten Island), the film offers a panoramic snapshot of the city’s streets, dive bars, precincts, bodegas, parks, and housing projects. Demonstrating, like few other films of the period, the documentary significance of narrative cinema, Serpico rightfully remains an object of obsession for many.

During this run of Lumet’s classic, Low Cinema is privileged to be joined by two special guests who have thought deeply about Serpico from different vantage points: on Monday, September 1, journalist Katie Honan — no stranger to (attempted) bribery herself — will shed some light on the political and historical background on Serpico and the Knapp commission and discuss the saga’s contemporary resonances. On Thursday, September 4, and Friday, September 5, researcher Mark E. Phillips will give a presentation on the film’s 104 locations and its broader production history.

Katie Honan is a senior reporter at the online news site THE CITY and a co-host of the FAQ NYC podcast. She is a lifelong Queens resident.

Mark E. Phillips is a New York native who has spent the last 15 years working in the film industry, both behind and in front of the camera. In 2016, he founded the website NYCinFilm.com which is dedicated to cataloguing filming locations of classic New York movies and exploring how they connect to the history of the city.

Dir. Sidney Lumet, 1973, USA, 130 min.

If you haven’t seen Sidney Lumet’s classic 1973 biopic of cop-turned-anti-corruption-crusader Frank Serpico — a piece of cinema so gritty and unflinching that its position among the greats of fiscal-crisis-era New York movies is practically set in stone —you can be forgiven. After all, you’ve had to witness a similar clown show throughout Eric Adams’s mayoralty. The days of the Knapp Commission, the investigative body that Serpico’s revelations brought about, may be over, but the most bloated police department in the country doesn’t seem to have learned its lesson. Just two months ago, Thomas Donlon, one of Adams’s erstwhile police commissioners (of which Adams has cycled through four in as many years) filed a federal lawsuit against the department, which, pulling no punches, he called “A coordinated criminal conspiracy” that is “criminal at its core.”

Of course, aside from Serpico’s eerie political relevance even half a century later, it also stands out as a convergence of many talented filmworkers’ crafts. Al Pacino, who would reunite with Lumet two years later for Dog Day Afternoon, gives a master class in the Strasbergian method, his performance at once so raw and so measured that it gave chills to even the most jaded critics. Screenwriters Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler contributed other titans into the pantheon of New York City cinema, titles no less seminal than Midnight Cowboy and Saturday Night Fever. And cinematographer Arthur Ornitz would go on to lens equally iconic — if somewhat mutually antithetical — portraits of the city in Death Wish and An Unmarried Woman.

But perhaps one of the most singular pleasures of watching Serpico today is its unmatched value as a time capsule of Gotham’s urban fabric in the early 1970s. Shot on location in four out of the five boroughs (sorry Staten Island), the film offers a panoramic snapshot of the city’s streets, dive bars, precincts, bodegas, parks, and housing projects. Demonstrating, like few other films of the period, the documentary significance of narrative cinema, Serpico rightfully remains an object of obsession for many.

During this run of Lumet’s classic, Low Cinema is privileged to be joined by two special guests who have thought deeply about Serpico from different vantage points: on Monday, September 1, journalist Katie Honan — no stranger to (attempted) bribery herself — will shed some light on the political and historical background on Serpico and the Knapp commission and discuss the saga’s contemporary resonances. On Thursday, September 4, and Friday, September 5, researcher Mark E. Phillips will give a presentation on the film’s 104 locations and its broader production history.

Katie Honan is a senior reporter at the online news site THE CITY and a co-host of the FAQ NYC podcast. She is a lifelong Queens resident.

Mark E. Phillips is a New York native who has spent the last 15 years working in the film industry, both behind and in front of the camera. In 2016, he founded the website NYCinFilm.com which is dedicated to cataloguing filming locations of classic New York movies and exploring how they connect to the history of the city.